[ad_1]

Mushroom foraging can be imposing for the beginner and rewarding for the seasoned veteran. Mushrooms are everywhere, tasty, and have great nutritional value. Oh, and some of them can kill you.

Alternatively to mushroom farming, foraging is not a hobby to go into lightly… It requires attention to detail and the dedication to seek professional instruction.

That being said, mushroom foraging can have significant benefits, including food, fresh air, and the opportunity to scout for much more than mushrooms (other edibles, animal signs, etc.).

I’ve been wandering the forests of the northeast for over a decade in search of these little gems. Each trip finds something new, be it a new mushroom or a new location.

In fact, I get as much enjoyment out of the time in the woods as I do finding my favorite edibles.

So how hard is mushroom foraging? In short, not hard.

You need to have a fair amount of knowledge of the parts of a mushroom, the general classes of mushrooms, and the various environments and seasons in which they grow.

Finally, there are a few optional tools that will make the job easier.

Take a few moments to join me in this article and ask yourself if mushroom foraging is for you.

Warnings and Disclaimer

OK, I have to start with a warning. Mushrooms can kill you. Eat the wrong one, and there are many, and your liver may melt and you will die.

If you’re lucky, you’ll just end up in the hospital wishing you were dead. Make no mistake about it, mushrooms are dangerous.

Before venturing into the woods and filling a basket, take a class taught by a professional forager. Even if you are 100% positive of your identification, have it verified by a seasoned forager.

Never eat a new mushroom without one or more educated opinions. If in doubt, leave it in the field for another day. The stakes are too high.

This article is not a substitute for professional education. This article is meant to generate interest in foraging mushrooms while emphasizing the need for instruction and guidance by expert mushroom foragers.

References

Like much in homesteading or prepping, you can never have enough reference materials. Mushrooms are no different. As mushrooms are a vast topic, I recommend several different books and other materials.

First, I recommend a few broad identification guides. Not that you will read these cover to cover (although I do recommend it), they are great to teach you the specifics of mushroom identification.

From habitat to anatomy to feature differentiation, they are perfect for educating you about the minutiae of identification that makes the difference between tasty and deadly.

Both the Peterson and Audubon guides are the classic identification bibles for the hobby.

They will introduce the concepts that I discuss below (gills, ridges, cap-stem attachment) as well as other identifiers such as spore size and shape, spore prints, and several others.

Disclosure: This post has links to 3rd party websites, so I may get a commission if you buy through those links. Survival Sullivan is a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program. As an Amazon Associate, I earn from qualifying purchases. See my full disclosure for more.

I recommend getting one or both guides and using them to verify/identify species you encounter in your yard or woods walks. Not to eat them, but as a means to sharpen your identification skills.

Alternatively, I suggest a local guide to mushroom species. This narrows down the species to those that you are most likely to encounter.

Both Audubon and Peterson have similar guides, and if there is one for your area, jump on them.

The advantage of having several guides is that each will have different pictures or drawings. The more variety of information you can get for an individual species, the greater the chance you will have for positive identification.

Finally, hit the local clubs and universities for guides, quick reference sheets, etc. for the most local information on your native species.

These are not a substitute for a complete guide, but as you learn the ropes, they are perfect for a quick field reference to narrow down a species.

These guides are not meant to be a replacement for professional instruction, rather, they augment what you will learn from a skilled teacher and reinforce the class materials while in the woods and at home.

Regarding references, I do not recommend phone or online apps for identification. They may give the good occasional hit, but they are not accurate enough to trust your life with.

What I recommend is posting pictures to Facebook groups, Reddit forums, and the like. When you do this, provide several pictures:

- The general habitat you found it including the still attached mushroom (deciduous forest, pine forest, on a log) as well as details that may not be apparent from the picture (e.g., beech or oak log)

- Pictures of the cap

- Picture of the underside of the cap (gills, pores, ridges, teeth, a vale where the cap was once attached to the stem)

- A picture of the inside of the mushroom (yes, cut it in half–this can be the difference between an edible puffball and a fatal amanita, or a choice morel and a sickening false morel)

And please, do not start with, “I found this mushroom, can I eat it?” Foragers hate that. The experts on these forums are very willing to share their knowledge. Don’t be an idiot and be thankful for their time.

Mushroom Anatomy

Without getting too into the details, there are just a few parts of mushrooms you need to be familiar with.

First is the cap. This is the fleshy top of the mushroom. In classic, mushroom shapes, the cap is on top of the stem and is round and somewhat symmetrical.

There are other mushrooms, such as the hedgehog, where the cap is neither round nor symmetrical. Cap shape and size can be primary identifiers.

Further, other mushrooms will have a cap or many caps without stems. These mushrooms generally grow in brackets\shelves with one cap over another, such as the highly identifiable chicken of the woods.

Next are the features under the cap. Most know mushrooms with gills. Gills are thin membranes radiating from the stem to the edge of the cap.

A similar but distinctive feature is ridges. Ridges differ from gills in that they are thicker and slightly wavy rather than straight.

Gills look like sheets of paper, while ridges look like wrinkles in clothing. For a comparison of ridges to gills, compare Chanterelles (ridges) to Jack-o’-lantern (gills).

Still, other mushrooms will have pores under the cap. These features look like a sponge. They are subdivided by pore size. Some are quite large, while others are barely visible to the eye.

Other mushrooms, in particular the hedgehog once again, has teeth under the cap. Arrayed like a fine series of icicles, the teeth look like no other features and are easily differentiated from the other spore-bearing surfaces.

A second identifiable feature of ridges and gills is how they join the stem. Differences to watch out for are ridges/gills that end abruptly at the stem versus ridges/gills that retreat up the stem, or travel down the stem. These minor differences count.

Next is the stem itself. Stems can be thick, thin, short, and stout.

Further, they can have attachments at the base (e.g., amanitas “hatch” from an egg and the leftovers of this structure remain) or ring near the top at the cap, also called a vale, where the cap was once attached.

Again, it’s the minor details that separate the healthy from the deadly.

Finally, there are some mushrooms that defy even these parts. In particular, the black trumpet that we will soon discuss has no cap, stem, or visible gills. Sometimes it’s the lack of features that makes one easy to identify.

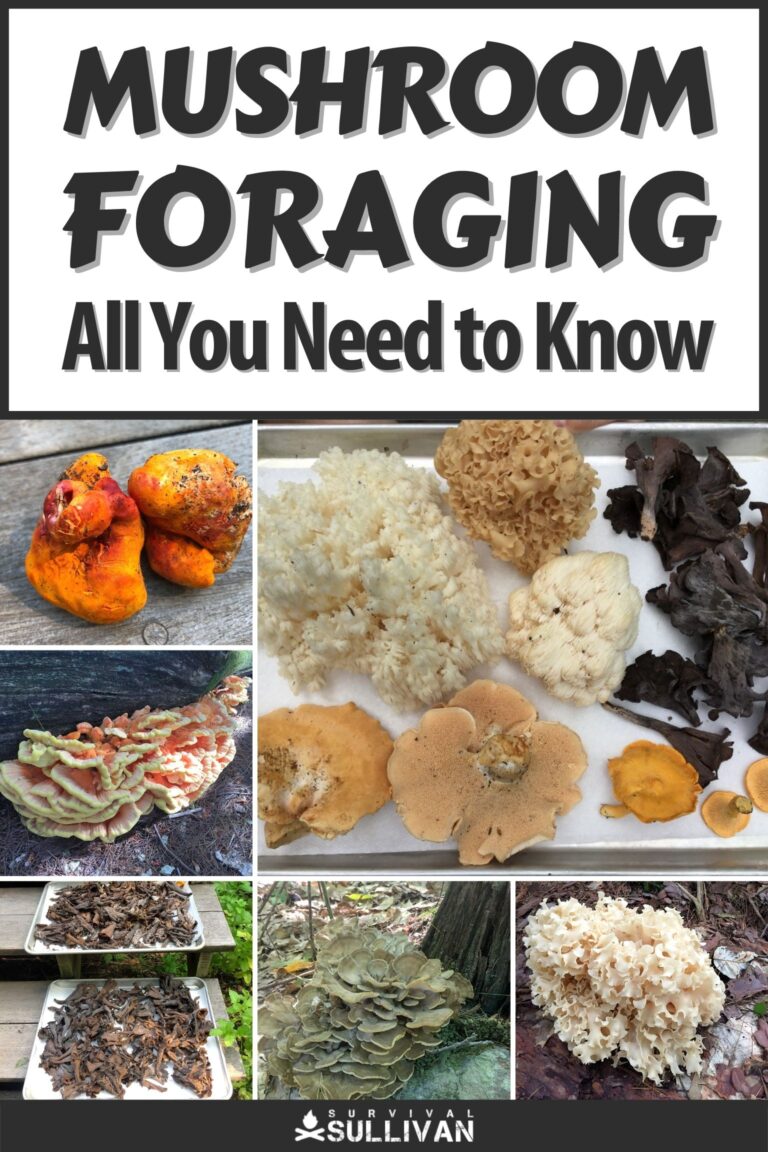

Mushroom Types

For this article, we will discuss three types of mushrooms: traditional cap and stem, shelf, and a few that defy these descriptions.

Traditional Cap and Stem Mushrooms

Cap and stem mushrooms have exactly that. You will look for a distinct cap, stem, and gills or other features under the cap.

You can find them growing alone or in clusters. Note the difference.

Not only do Chanterelles differ from Jack-o’-lanterns in their ridges, but Chanterelles grow singly while Jacks grow in clusters. Again, a minor difference, but Chanterelles are delicious and Jacks will send you to the hospital.

Cap and stem mushrooms are further defined by the structures under the caps. There is an entire class of mushrooms, boletes, that have spongy pores rather than gills.

Get used to picking and flipping your mushroom over to add to your identification.

Shelf Mushrooms

The next broad class is bracket and shelf mushrooms. These grow in layers or stacks, usually on a tree or a log.

Most have no visible stem, such as the Chicken Of The Woods, or the Hen Of The Woods, while others, Oyster mushrooms, have the faintest hit of a stem.

Again, these can grow singly, such as Reshi, or in clusters.

Other Mushrooms

Finally, there are “other” mushrooms. As noted, the black trumpet has neither a cap nor a shelf. Cauliflower mushrooms look more like a pile of egg noodles.

Finally, Bear’s Tooth and Lion’s Mane would look more at home under the sea with coral rather than growing on a tree.

Pay attention to the features of mushrooms, but don’t limit yourself to traditional cartoon shapes. Mushrooms often defy the imagination.

Location, Location, Location

OK, where is the best place to forage for mushrooms? That’s like the physical description of mushrooms, isn’t that easy. It all depends on the mushroom.

Foraging isn’t as much about learning about the mushrooms as it’s learning about the world we live in.

Some mushrooms grow in very distinct habitats. Some will grow on a single species of tree. Others require a combination of elements.

MulitipleSpeciesOneWalkThese classes of mushrooms are called mycorrhizal. Mycorrhizal mushrooms are found best by looking for the right environment. In my location, Black Trumpets are found growing on or near moss and near beech trees.

When scouting new spots for Black Trumpets, I look up more than down. Hen Of The Woods mushrooms are found mostly on dead red oak stumps. Again, look for the trees and find the mushrooms.

Other mushrooms, called saprophytic, grow on dead and decaying matter.

Pheasant Tail and Turkey Tail mushrooms can be found on nearly any dead log. You can find these almost anywhere as microclimate matters more than forest makeup.

Mushroom foraging will benefit as much from learning your forest ecosphere as learning the mushrooms themselves.

Mushroom Seasons

Just as important as location is seasons. Most mushrooms prefer one season over another. Early spring is the time for morel mushrooms.

Chicken of the Woods, around here rarely starts before August, however I know of one log that is always ready on July 4th. Hen of the Woods is a mid to late-fall mushroom.

So, what are the best seasons for foraging mushrooms? It depends on the mushroom, but late summer to early fall is better than spring and early summer. In my area, I don’t start looking until late July and stop in October.

Foraging Tools

A trip into the woods for mushrooms need not be complicated or require a lot of equipment. A reference book or two, a knife, a brush, and a bag or basket are all you need.

Always bring a reference book. Once I left it at home and came across an interesting find. When I got home, my wife said, “I think that’s a cauliflower mushroom”.

Well, it was a mile long hike back into the woods to get it. Had I brought the guide, I would have saved the steps. It was worth it though!

Next are a knife and a brush. This doesn’t have to be anything fancy. The knife is for harvesting and trimming while the brush is to remove any forest duff.

It’s easier to clean the mushrooms as soon as you pick them vs after they’ve been in your bag for a few hours. I’ve linked to a nice little knife-brush combo. They make the job easier but aren’t necessary.

I recommend a mushroom bag, something like the following. If not, then at least get a lingerie mesh bag.

The advantage of these bags is that they allow the spores to float out of the bag while you walk. You can be the mushroom equivalent of Johnny Appleseed.

10 Edible Mushrooms You Can Forage

1. Chicken Of The Woods (Laetiporus sulphureus)

Chicken of the Woods is one of the best starter mushrooms. Chickens check all the beginner boxes.

They grow in a limited environment. They are brightly colored. They are big and easy to spot. Finally, nothing looks like them in the forest.

Chickens are a shelf fungus that grows on dead/dying oaks and occasionally pine or hemlock. They also grow on stumps. Finally, they may grow out of the ground on an old, buried stump or rotting roots.

Geographically, they grow throughout the US and Europe and can get quite large.

Anatomically, they appear as stacked shelves (rather than traditional cap and stem) that are yellow to orange on the top and yellow to white on the bottom. The fan-shaped shelves have small pores/tubes underneath.

Young chickens are best as they are soft and tender. More mature ones will be larger and tougher. We favor a simple pan fry for young chickens with lots of butter, olive oil, and thyme.

Older mushrooms head to the canner with a simple brine, garlic, and more thyme. Both have a texture similar to chicken breast.

Late summer through early fall is when I find most chickens. They grow year after year on the same logs, and I have established hunting routes around their location and timing.

2. Chanterelles (Cantharellus cibarius)

Chanterelles are one of my favorites. They are also easy to spot in the forest because of their bright color. While they are easy to differentiate from a poisonous look alike, this process requires close inspection.

Chanterelles are yellow to orange, and grow singly or in small groups of two or three.

Finally, they have ridges and not gills. Ridges appear as folds under the cap running down the stem. The underside looks more like it needs to be ironed, as it is particularly wrinkly.

There are several species of this mushroom, all with similar characteristics, so I’ve included two links, one for the general genus and the second for the most common species.

There are two look-a-likes to this tasty edible. The first is the jack-o’-lantern. These grow in dense clusters, have gills, and glow in the dark. Really, they do and I’ve been looking for them for years just to get a picture.

The second is the false chanterelle. Slightly different in color, cap shape, and gill pattern make this one that you need to spend a little time looking at each mushroom to make sure you avoid intestinal distress or hospitalization.

Chanterelles grow year after year in the same location. I generally start looking in mid-July all the way through October.

3. Hedgehogs (Hydnum repandum)

Hedgehogs are one of the few mushrooms that I can find in volume. They are tasty and preserve well via drying.

The most distinctive anatomical element is the teeth under the cap. The teeth are present as mini icicles (shown well in the Wikipedia link below).

Very few mushrooms have teeth and these are the number one feature that makes them stick out from the rest of the forest.

Second, I rely on color and shape. The color is that of cream. Not white, not brown, not even tan. Hedgehog mushrooms occupy a space between these colors.

The shape is a standard cap and stem, however, the cap is uneven with a wavy edge rather than perfectly round.

In the north-east US hedgehogs start in mid-August. I find them in the same areas, however, year to year, their availability varies with the amount of rainfall.

For dry years, I only find them in my tried-and-true spots. Wet years have me finding them everywhere.

4. Hen Of The Woods (Grifola frondosa)

Another bracket/shelf fungus is the Hen of the Woods. This was the first foraged edible that I was ever introduced to.

Growing at the base of oak or maple trees, these fungi can get huge. Often growing more than a foot or two in diameter and easily 20-30 pounds.

Also called a Maitake, hens have many intertwined shelves or bracket structures. The tops are light brown to dark brown. The cap bottoms are white with dense pores.

Growing on a minimal number of wood species, hens are perennial as they grow in the same spot year after year until the nutrient in the host tree is spent. They are a late summer and fall mushrooms.

5. Old Man Of The Woods (Strobilomyces strobilaceus)

The old man of the woods is the first and only Bolete mushroom on this list. Boletes are a family of mushrooms with traditional caps that host pores rather than gills or ridges.

A quick look under the cap will quickly differentiate a bolete from any other mushroom.

The old man is defined by its dark, almost spikey surface. From stem to cap, the look is distinct. They honestly look like burnt meringue.

Growing mostly in deciduous forests, old men are found throughout the summer and fall.

6. Cauliflower (Sparassis)

Stumbling across a cauliflower mushroom is a lot like walking up to a pile of egg noodles in the middle of a pine forest.

What are egg noodles doing in a pine forest? Just a big Cauliflower mushroom…

The similarity doesn’t end there. They look like egg noodles and have the same texture.

Growing in a large clump, they are easy to harvest as you just cut their small attachment point from the ground. With all the folds, nooks, and crannies, they collect dirt, debris, and bugs.

They are a sturdy mushroom and are easily cleaned with little or no damage as you wash them and pull them apart.

I’ve only found two or three in my years of foraging. They grow predominantly in pine forests. They are great, simply sauteed up with butter or even better batter fried.

7. Black Trumpets (Craterellus cornucopioides)

Black trumpets are a rare edible however, I don’t know if they are actually rare or just, really hard to find.

When looking for a black trumpet, you are either really low to the ground or looking for a few little spikes. Or you are looking at your feet, trying to find a black hole in the forest floor. They are truly elusive!

Trumpets grow around moss and beech trees. I look more for the environment than I look for the mushrooms. They grow in the same area year after year and I try to add a few new spots each year.

Trumpets also are highly dependent on the weather. In dry years, I’m rarely lucky enough to come away with more than enough for a single meal. In wet years I’ve come away with over 7 pounds from a single hike in the same area.

Trumpets are great, like most mushrooms, with butter and thyme. They have a woodsy flavor and go great with game meats.

Further, they dry well. Rehydrate them and discard the water (it is bitter). Alternatively, grind and crush them up and mix them in with eggs, rice, polenta, etc.

8. Bears Tooth (Hericium americanum) / Lion’s Mane (Hericium Erinaceus)

Bears Tooth and Lion’s Mane are a wonderful starter mushroom. Tasty and there is absolutely nothing like them in the forest.

I generally spot them from 50 to 75 yards away as they are brilliantly white.

These two strange-looking fungi grow mostly on beech trees, and to the beginner, they are one in the same mushroom. While there are minor differences, it doesn’t much matter.

Looking like bright white collections of little icicles, they can grow to the size of a soccer ball, although smaller clumps are much more prevalent.

They are very watery and are easy to pick off of standing beech trees. When they grow on down logs, trim them to remove leaves and to wash them to remove bugs.

With a texture like a crab and a flavor that can be similar, they are well sauteed or, our favorite, cooked for an hour in spaghetti sauce.

9. Puffballs (Lycoperdon perlatum) / Giant Puffball(Calvatia gigantea)

Puffballs seem to be everywhere. While they don’t have a lot of taste, their neutral presence aid in cooking them in a variety of ways and with a variety of other foods.

The telltale sign of an edible puffball is the pure white, featureless center. Cut them in half and they should have no hint of brown, grey, or black.

Common puffballs (perlatum) are small, with an indistinct stem and small nubs over the surface.

Giant puffballs are smooth and huge. Often growing to the size of a volleyball. I’ve often seen these sliced thick and used as pizza crust.

Small puffballs can look like immature Amanitas. Some Amanitas when eaten will kill you. No joking here. Dead.

If you are going to forage, puffballs are very familiar with both species, especially the signs of an Amanita (smooth surface, egg shape, distinct cross-section when cut).

10. Lobster Mushrooms (Hypomyces lactifluorum)

What a wonder it is to find a lobster mushroom. Lobsters are actually the combination of either a Lactarius or Russula and a second parasitic fungus. The result looks, tastes, and smells just like lobster.

I never specifically look for them, as they are a matter of surprise more than planning. I do, however, keep my nose open for the smell of lobster. They can smell quite strong and can be found from tens of feet away.

Just like lobster, slice, and cook with butter.

5 Mushrooms You Should Avoid

1. Amanitas (Genus Amanita)

The Amanita Genus is known for having some of the most problematic species. From the mildly discomforting Fly Agaric (muscaria) to the deadly Destroying Angel (bisporigeria).

While there are a few edible species, the differences are minute and many take experts to identify.

2. Boletes (Genus Boletus)

This is not a particularly dangerous genus however, there are several edible species and many species that can make you sick.

The identifying feature of this genus is an under-cap surface that is spongy and filled with pores. The complication is in the subtle differences between species.

Some edible samples stain blue when cut, inedible species also stain blue, however at a different rate. There are no general rules for boletes.

This is definitely a species for more advanced hunters.

3. Jack-o’-Lanterns (Omphalotus illudens)

Foragers often mistake Jack-o’-Lanterns for the choice of edibles chanterelles. While there are distinct differences, confusion still happens.

They can also be confused with Honey mushrooms (Genus Armillaria). Eating jack-o’-lanterns can cause severe gastric distress that may lead to hospitalization.

4. Russulas (Genus Russula)

My grandfather used to take us out foraging for wine cap mushrooms. It was a skill he brought over from the “old world”, Poland. As I got into mushrooms, I determined he was most likely forging Russulas.

This genus holds several species with mixed edibility and very similar features. They cross over with other non-edible species when immature or old. Again, this group, while there are awards to be found, is best left to the experts.

5. Little Brown Mushrooms (LBMs)

Not as much of a joke as it sounds, LBMs is a generic term for the hundreds of species of little brown fungi that require expert analysis to identify.

The problem is in the vast numbers of various similar mushrooms. While there may be one or two that are edible there are tens or hundreds that aren’t.

Wrapping up Mushroom Foraging

I often get asked by a friend pointing at a random mushroom “Hey is this edible?” “Yes, at least once. The second time might be difficult, as you might be dead”.

Mushrooms are not to be taken lightly and they are not to be experimented with. During my last class, we found and identified over 150 species.

25% were edible, 25% were edible with precautions (specific preparations are required). 25% were medicinal, and the remaining would put you in the bathroom, hospital, or morgue.

Cautions aside, there is a lot to benefit you in the forest. From the fun and fresh air to the excitement of finding a new patch to the meal at the end of the walk, mushrooms are rewarding.

Have I found a mushroom on every trip? Nope. Have I had fun, logged miles, and been better for the hike? Definitely.

Start slow, find an expert, gather a few reference books, and head out to the woods!

[ad_2]

Source link

Get more stuff like this

in your inbox

Don't Be Left Unprepared

Thank you for subscribing.

Something went wrong.